Hi, everyone!

If you paid any attention to management twitter at all in the past week, you heard about how Basecamp started the week by announcing - in a public blogpost! - a new internal policy about how all committees in the company including the new DEI committee was disbanded, and how politics was now forbidden from discussion inside Basecamp or on official accounts, and how it ended the week with 30% of their 50-some-odd company leaving.

I swore I wouldn’t get drawn into that morass for the newsletter, because “managers behaving badly” isn’t the beat I want to be on - it’s depressing, plentiful, and frankly there’s precious little new to be learned from any given episode. There’s a million ways that managers can do things poorly, with many fewer to do things right, and helping managers do things right is where I want this newsletter to be.

But the actual underlying story of what was behind the Basecamp fiasco ended up being being so mundane, so petty, and such an easy trap to fall into I kind of feel like it’s worth addressing.

Back in the day, started by a Basecamp employee who’s since departed, a list started circulating of “funny names” of customers. It kept cropping up and being updated. After the events of the past year, and with the forming of a DEI committee, complaints about how deeply not ok that was started to surface, and calls came for the founders to address it in some way. The founders didn’t want to do anything, someone who hadn’t always behaved completely properly in regards to discussions around those names continued to advocate for something to be done, and the founders responded by pointing out past misdeeds, banning further discussion, and the blog post announcing that any political discussion was verboten, all decisions are made by them, and shutting down committees.

As a manager, our main job is to listen, to make some decisions and enable many others to be made, and to constantly be alive to the possibility that we might be grievously wrong about something. I like to imagine that coming from the world of science, we’re more attuned than the most to the possibility that we’re incorrect. But it gets harder to stay so attuned the longer that people are deferential to you; it takes active practice.

The Basecamp founders could have avoided a self-inflicted minor catastrophe (how would you deal with 1/3 of your team being gone tomorrow?) by just listening to their team, taking the loss even if they didn’t think personally it was that big a deal, and moving on. But they doubled down, and now thousands of articles, including ones in obscure management newsletters, are being written about them giving a postmortem and an incident report.

It’s not easy to back down as a manager, and it’s easy to get personally invested in individual decisions. But it’s not about us; it’s not even necessarily about the team; it’s about the impact we want our team to have. We have to be willing to walk back poor decisions when they get in the way of achieving the things we want our team to achieve.

Anyway, with that, it’s on to the roundup:

Managing Teams

A thorough team guide to RFCs - Juan Pablo Buriticá

We’ve written before about design documents architectural decision logs (e.g. #25) and using collaboration around documents as a form of asynchronous meeting (e.g. #41). Usually the thinking is that someone in charge has initiated the document. Buriticá writes about team member-initiated requests for comments as a proposal for a change or the creation of something new, which can then go through a comments phase like a PR, and an approval phase where whatever decision making process is appropriate plays out and people get to work implementing the proposal. In this respect it’s like a Python PEP or a W3C RFC.

This approach is very consistent with a model of delegating to and developing your team members - turning every team member into a technical leader by having them propose, revise, and gain support for technical directions in their area of expertise.

Inclusion in a Distributed World - Christoph Nakazawa

Most of our teams are going to be moving to some kind of hybrid model of distributed and office work, and this mixed approach is notoriously difficult to get right. So it’s important to start figuring out now how to make the transition and what the future will look like.

Nakazawa talks us through some of the issues - principally, if there is an “in office” and “remote” split in the team, it is really really easy for the “remote” team members to become an afterthought. On top of the obvious stuff - when calling into meetings, everyone has to call in from their own device, so everyone experiences the meeting as a virtual meeting - there have to continue to be structures in place to build a cross team culture.

Nakazawa talks about maintaining virtual team social events, and including team culture as part of retrospectives; but also of doing planning together as a team, and maintaining asynchronous, document based collaboration and decision making (like RFCs above).

We’ve largely learned how to do these things in the coming year; in the rush to get “back to normal” we don’t want to loose these trickier but more flexible and powerful collaboration skills we’ve learned. If we keep using them and keep those muscles in shape, we’ll be able to hire remotely and still maintain the strengths of our skills.

Managing Individuals

How to Run Effective 1:1s - Luca RossiThe big guide to One on Ones (1:1s) for Managers - Matt Nunogawa

It’s always good to refresh the basics, especially when hearing from someone new.

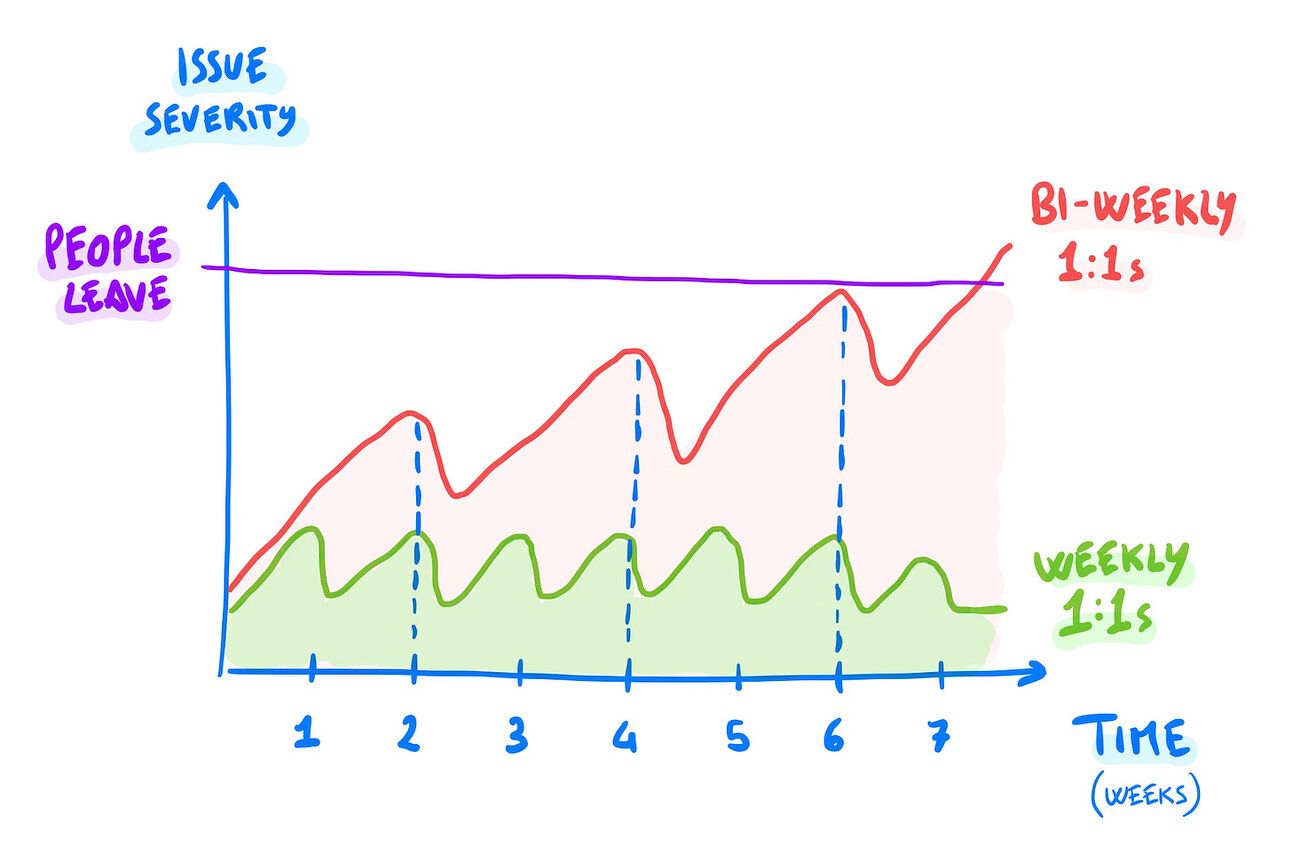

Rossi emphasizes, correctly in my opinion, the relationship-maintenance aspect of one-on-ones - maintaining the lines of communication is at least as important as what is communicated in any particular one-on-one. He also has this nice image about how having a scheduled opportunity to touch base frequently makes it much easier to make nudges and keep things on course than having less-frequent one-on-ones (or worse, not having them at all):

Both are good short reads, especially if you’re not already doing routine one-on-ones.