A reader wrote in to ask:

We have a new summer intern starting in a few weeks who I will be directly supervising. Although I have been the technical/project lead on various projects throughout my career, this is my first time having a direct report (even though it will be temporary!). I was wondering if you had any “go to” or favorite literature for managing in a technical setting.

Congratulations to them, and this is a great question. It’s such a great question that I’m disappointed to discover that I didn’t have handy resources to immediately share with them, and I’d love to hear what your recommendations are.

Probably the two most common ways people find themselves managing is to be promoted to lead their existing team, or the more gradual approach which is to start with one or more interns/grad students/etc - very common in highly technical fields.

But very few of the resources I see are for this second case. Which is weird! A new intern or trainee for a summer is a really common starting point for a lead/manager, and it’s something I greatly encourage, for a number of reasons (like improving your hiring and onboarding pipeline.) But it’s different in key ways than managing a regular employee:

The balance of goals is different - while “career development” and “work of the team gets done” are both important for all staff, the balance shifts significantly towards “career development” for trainees. There is correctly lot of emphasis on making sure the intern has something to show on their CV at the end,

Because of the time-limited nature of an internship, the scope of is usually much narrower, and ensuring you have very crisply scoped projects or tasks for the intern ahead of time is vital,

Interns are much earlier on in their career path, so they are a lot less independent both in terms of domain knowledge and just general functioning in a work culture. So there’s a lot of teaching of domain knowledge, modelling of work culture, and the interns benefit from and require more frequent feedback even than regular employees.

(By the way, I want to emphasize that last one. Interns WANT FEEDBACK. The last batch of co-op students our team mentored, when we had a “first month review” - it’s in a checklist I share later on - all said that the thing they wanted more of was feedback and evaluation. They were high achievers, and are doing the internship to develop their skills. They craved knowing how they were doing and how to improve. If they didn’t hear that they were doing well, they worried they were doing badly. Don’t deprive your interns, or your full time staff, of feedback!)

Some of these things make managing an intern easier, or at least front loads the work (clear tasks) and some make it harder (much more junior). And of course because it’s often one’s first management responsibility, it’s harder still.

So we have to:

Plan to spend a lot of time supporting the intern, particularly but not solely at the beginning

Be very clear around goals from the outset -

What is the main goal for the intern: what deliverables will they provide, what will they learn

What is the main goal for the organization from the internship: getting things done, maybe, but also a hiring pipeline

Provide learning resources ahead of time for the intern

Realize that an intern can accomplish a lot given the resources and support

For new managers of permanent full-time staff, I usually recommend three big things to focus on - one-on-ones (to build and maintain trust and lines of communication), feedback (to set expectations and keep people on track), and delegation (letting go of tasks).

But one’s probably not going to delegate huge chunks of one’s job to an intern (they won’t be there long enough and they probably have fairly well-defined work to do), and while one-on-ones are worth doing, you’ll probably be keeping a pretty close eye on their work, so the emphasis will be different. So my suggestions for starting with an intern would be to focus on two things, feedback and one-on-ones as a communication mechanism.

Practice giving super frequent feedback (say 5:1 or 10:1 positive:negative, and at least one piece of feedback daily) - my feedback guide and resources may help

Take a look at any of the one-on-one resources on my one-on-ones guide page, or any others you may have seen; after the first week or so start having one-on-ones weekly (I say after the first week because you’ll probably be talking with them roughly daily for the first week).

The usual one-on-one formula typically has some time put aside for the future/career development - I’d say if you want to make it a really valuable experience for the intern (and they will tell their classmates, which makes a significant difference when getting your next interns) one useful way to spend some of that time is, in the first few weeks, finding out what they want to be doing next, and then as they start accomplishing things, helping them express those as resume-friendly bullet points in a running list through the term, ideally with something they can show as a portfolio. It helps keep them motivated, and helps you know what’s important to interns these days which in turn helps you advertise for them better.

Also, towards the end (assuming of course you’re happy with how it went) if you sketch out a couple-paragraph letter of reference for them describing what they did and post that as a LinkedIn recommendation, that goes a long way too (and as a side effect leaves you with a record of what’s been accomplished, and a reminder about who they are in case they end up applying for a job in the future).

The other big thing is offboarding the intern. We all know this intellectually, but a recurring issue with short term team-members is making sure that whatever knowledge of what they’ve learned and created doesn’t disappear with them. Having a really robust plan for how they’ll document things, and verifying it repeatedly towards the end of their time with you is essential. We all say “well yes, of course” when that’s brought up, and yet we are all without fail surprised when they’ve left and something isn’t documented and no one knows how they’ve done something. Having some process involving them giving walk throughs, demos, talks, or whatever to someone on their way out both helps them with developing professional communication skills and helps you collect needed knowledge.

One way to approach this is to have a documented process for hiring, onboarding, supporting, and offboarding the intern. The first time or two through the process, it’ll be laughably off-base, and that’s fine. Once something is documented the process can iteratively improve over time, which is the key thing. It’s really hard to improve a process that isn’t documented. If it’s documented, you can update it through and at the end of the process.

To try to help, the question spurred me to clean up and make suitable for sharing a starting-point intern onboarding/support/offboarding checklist. It’s just a google doc checklist-style list of bullet points, and it geared towards a more project-based software development internship, but hopefully it will be useful to other intern managers as well.

So how about you, gentle reader? Do you have internship resources, tips, or advice for the reader who posed the question, or for the readership in general? Please let me know - just hit reply or email to [email protected].

With that, on to the roundup! It’s a bit short today, because it’s been that kind of a week.

Managing Teams

Having Career Conversations - Joe Lynch

As I mentioned a couple of weeks ago, mentorship only goes beyond cheap advice-giving if you’re willing to dig in a little deeper to the questions and answers being presented to you.

Part of every manager and lead’s job is to support the career development of their team members. And that means having career conversations with them. That means digging deep. Lynch prods us to go beyond the superficial of what the team member says their goals are, and to understand the (usually multiple) motivations behind the goals. People, especially but certainly not only juniors, often trip over the XY problem in setting their career goals. They ask for help with X so they can do Y, when it’s not a given that Y is even what they really want, much less that X is the way to get it.

Beyond that, Lynch emphasizes:

Trust is needed for these conversations

These are ongoing conversations

There needs to be shared expectations about the level of confidentiality of the conversations

You have to be prepared for the high likelihood that once enough time passes, these conversations will eventually lead to conclusions that the team member will have to pursue their goals outside of the team or even the organization. That’s ok. People happily moving on is good and healthy. A team of “lifers” isn’t a healthy team, and shouldn’t be a goal.

Lynch gives a number of concrete suggestions, both tactical and more long term, for having these conversations, and if the topic is of interest it’s a short read.

We’ve talked about how candidate packets (e.g. #75) can be a useful part of the hiring process — that documents are posted about the job and hiring process, either (ideally) publicly or as something that every candidate who makes it past initial screening (say) gets. This is a great way to make your organization look more together (and thus more attractive to candidates), and to build alignment across the hiring team about what happens next.

Here’s a sort of FAQ for an organization, Interviewer Questions for “Time by Ping” , based on one of those lists of “Questions you should ask when applying for a job”. Some of the questions are fairly pointed! Being willing to answer those questions in a straightforward way, unprompted and publicly, is another way to make your organization stand out from the 3.2 zillion other orgs hiring for technical computing and data roles.

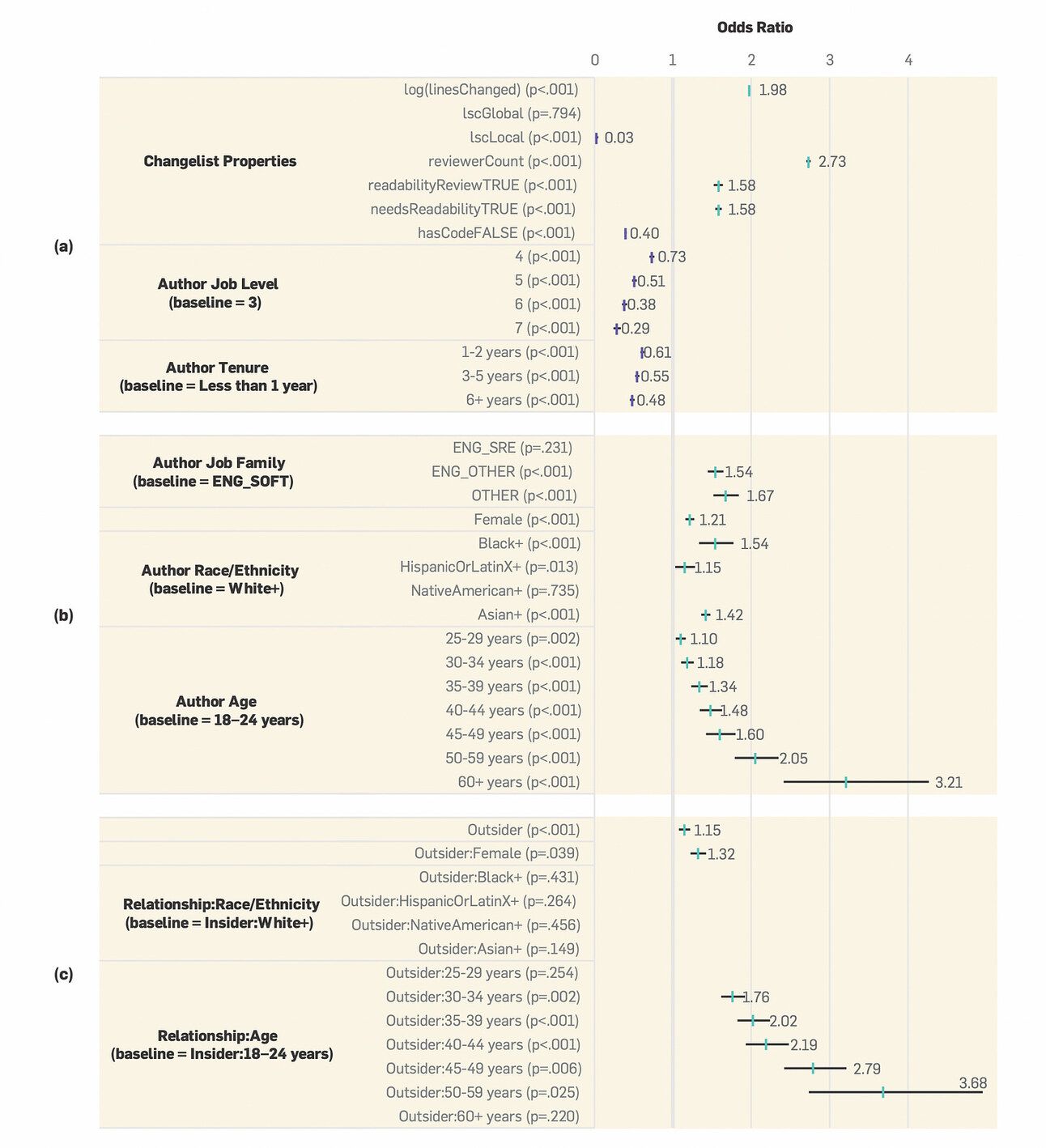

The pushback effects of race, ethnicity, gender, and age in code review - Emerson Murphy-Hill, Ciera Jaspan, Carolyn Egelman, Lan Cheng, Comm ACM 2022

This is about software, but it crossed my desk and applies more generally.

When we’re assessing the merits of a contribution (and by extension assessing references etc discussing a candidate’s merit), we need to be aware of these effects - non-white, non-male, and older colleagues get significantly higher pushback for contributions, controlling for number of lines changed, readability, and other effects.

Managing Your Own Career

Managing Your Manager - Brie Wolfson

Back in #86 we had an article by Roy Rapoport about manager “guard rails”, introducing us to the idea that there are spectra people tend to fall on when they are leading, like “freedom vs guidance” or “caution vs speed”. There’s no intrinsically bad side to either end of those spectra, although they can be better suited for some environments than others (nuclear plant safety equipment manufactures tend to avoid “move quick and break things” sorts of leaders in their technical staff, one supposes). Rapoport’s article talked about the different failure modes for leaders and the far ends of those spectra, and that you should have ways of detecting if your tendencies are causing problems.

In this really nice article, Wolfson gives a deeper typology of managers (but it could also be stakeholders, or even peers) along six dimensions:

Develops people ⇌ Delivers outcomes (do they tend to favour developing the people, trusting that over time that will lead to better outcomes, or do they favour focusing on the outcomes, and trust over time that that will provide opportunities for people growth?)

Craft ⇌ Machinery (do they tend to preferentially focus on the work, or the processes around the work?)

Uphold conditions ⇌ Challenge conditions (how likely are they to favour stability in the organization vs improve the organization?)

Assigns tasks ⇌ Assigns goals (In Rapoport’s version, “context vs control”)

Compassion ⇌ Hero (Roughly, provide support vs provide answers)

Prefers to see Raw Materials ⇌ Finished work

She also gives very detailed advice about successful ways of working with people who lean strongly to one side or the other of those spectra. The advice is very actionable and helpful; the article is worth reading in its entirety.

Making operational work more visible - Lorin Hochstein

This is about a particular type of work, but there’s a bigger lesson here on the undervaluing of supporting or glue or infrastructure work compared to “core” work. One of the huge downsides of such work is that when everything goes well, it’s invisible.

Hochstein suggests giving higher visibility to problems that don’t happen, and with routine improvements behind the scene:

Here’s the standing agenda for each issue: Brief recap, How did you figure out what the problem was, How did you resolve it? Anything notable/challenging? (e.g., diagnosing, resolving)

Getting in the habit of writing up and sharing — internally and externally — all the routine but notable work of has the same benefits of writing up big issues that arise. It improves transparency, is generally pretty interesting to a small subset of users, it builds a knowledge base, and it builds trust.

That’s it…

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your team,

Jonathan