Hi!

Last week I talked about the purpose of a meeting, and how for recurring catch-all meetings like team meetings, each agenda item might have its purpose.

This week I want to talk about how to make sure how people are engaged during the meetings. To keep people engages, there needs to be regular, valuable, opportunities to contribute and interact.

As people of science who have become team managers or leads, we understand the importance of considering our audience's needs when giving a talk. We tune the topics to local interests, we adjust the amount of background information to be appropriate to level of familiarity we expect most of the audience to have, we make sure there's time for Q&A so that there's interactivity. We learn this early on, whether it's explicitly taught to us or not, because (at least in person) we get very rapid feedback when a talk isn't landing - people start looking confused or bored, tune out, and start doing work or messing around on their phones.

We should put at least the same amount of thought into our meetings, and for the same reasons.

Having a purpose for the meeting and for each agenda item is a good start! But if we want our attendees to be engaged, the time must also be valuable and the meeting engaging to them. Otherwise, they will disengage and tune out. It is super difficult to bring them back into actively participating in the meeting once they're checked out.

And we care about that, right? There's no point in having them attend our meeting if we don't care whether or not they're engaged during the meeting. It wastes their time and saps our credibility as someone who runs good meetings.

Our team members' and colleagues' time is valuable. Every hour spent in a meeting is an hour not spent directly supporting research. Meetings are important tools of collaboration, but that collaboration can only happen when people are participating. Multiple people being routinely disengaged from a meeting, or only attending because they feel obliged to, is an engine warning light indicating that something is wrong with the meeting. We can fix it with a little thought and experimentation.

Attendees Should Find Meetings Valuable

We have all been part of meetings that weren't valuable to us. We know how that feels, and it's not great. We had to stop in the middle of whatever we were doing, and attend something where there's no place for us to contribute, the information being shared isn't relevant with us, and what useful information is being shared we could have just as easily read in an email at a time that was more convenient to us.

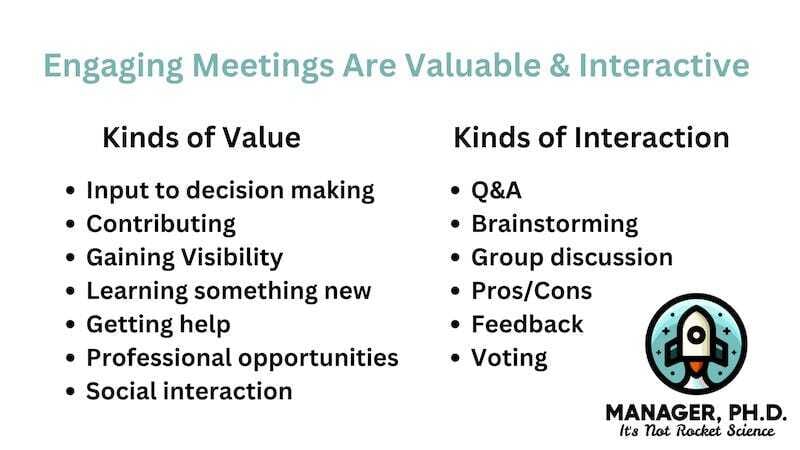

There's a lot of different ways that we or other attendees could find an agenda item valuable:

Having input into decision making

Contributing to an outcome

Gaining visibility for our work

Learning something new

Getting help with a problem

Professional opportunities

Social interactions with colleagues

In "catch-all" meetings like team meetings, some items might be less valuable to them than others. But everyone attending should be getting some value from most of the meeting. If that's routinely not the case, that's a good sign that the meeting needs rethinking or that parts of the meeting should be broken out into one or more smaller, more focussed meeting.

You're An Attendee, Too

It's ok if a short agenda item primarily benefits us. Maybe we want to give a quick broadcast announcement with no discussion necessary about some new item people should be aware of. Or as part of a larger meeting we want to get the sense of a few affected people about some issue, and rather than contacting them individually we quickly ask them while everyone’s together.

Efficiently making something short easy on us as managers or leaders isn't bad. But if a significant chunk of the meeting is routinely about making things efficient for us personally rather than being useful to the attendees, we musn't be surprised when it starts taking a lot of effort get those other people to participate on items where we do need them to be more collaborative.

Engaging Meetings Have Regular Valuable Opportunities To Interact

Synchronous meetings are useful principally because they provide the opportunity for high-bandwidth, low-latency interaction. That opportunity comes at significant cost - everyone attending has to stop what they're doing at some chosen time and join the meeting. But the possibility for interactivity is most of what makes synchronous meetings useful as a collaboration tool.

Luckily, it's also what makes meetings engaging to be a part of.

Regularly spaced and valuable opportunities to interact is key to meeting engagement. It's those parts of the meeting where people can participate that boosts us up and helps us stay focused and engaged in the conversation throughout the meeting.

Having routine discussion or activities that require collaboration are vital to keep us engaged. Q&A, group discussion, round tables, giving feedback, voting, brainstorming; a well-crafted agenda has slots for these activities spaced throughout the meeting.

Some forms of interaction may well fall flat with your team. There's nothing wrong with that; groups of human beings differ widely in our social norms and personal preferences. We're people of research, so we're good with experimentation. Try things, see what works, and use that information to try new things.

Even with relevant valuable agenda items, and frequent useful opportunities to interact, we can only maintain our enthusiasm and engagement for so long at a time. Meeting sessions longer than 90 minutes (maybe longer in person and almost certainly shorter purely virtual) likely benefit from having a break scheduled in the middle somewhere. Taking breaks throughout the meeting gives people a chance to refreshes their mind a bit, which helps us to stay attentive and focused during the rest of the meeting.

It's Easier For People To Interact If They Know What Will Be Asked Of Them

Some people find it hard or at least uncomfortable to think on their feet in front of others. Even those who are quite comfortable doing so will have better and more polished contributions if they've been given some time to think about the topic a little bit before hand.

So even for recurring meetings with standing agendas, pre-circulating the topics that will be discussed and what will be asked of attendees, and any necessary materials to inform those discussions, will improve our meetings. The discussions will be more effective for us, and more comfortable for some of our team members.

All Of This Can Be Overridden by the Meeting Purpose

The above is general guidance and principles. Any or all of it can be overridden by the purpose of the meeting.

Sometimes, our (or others') presence in the meeting can itself be the point. There's an article in the roundup below about using a brief synchronous meeting, with little interaction, to share bad news promptly. There, the purpose is to share bad news with the seriousness and respect it deserves. Doing it synchronously with little interactivity serves that purpose even though it flies in the face of the general-purpose guidance above.

Other times, people showing up can serve social or encouragement purposes. Maybe a trainee needs practice giving a talk in front of a friendly audience. Sitting through that awkward first version of the talk won't be the most directly valuable to us thing we'll do that day, but is very valuable to the person giving the talk. So we do it and ask other volunteers to attend, we give them a little practice and confidence handling some softball Q&A at the end of the talk, and give them discrete feedback afterwards.

The purpose of the gathering should always be primary.

Always Get Feedback

Every meeting can always be made better.

Regular meeting retrospectives can help the group shape how to run future meetings. And discussing meetings in our one-on-ones with team members can help bring to the surface issues that people might not feel comfortable raising as part of the group.

Getting regular feedback on the meeting helps us iteratively improve. It also gives us some confidence to try new things in our meetings, because we know we'll find out quickly enough if it didn't work.

Resources

Resources I really like for this include:

The Workshop Survival Guide by Fitzpatrick & Hunt and The Art Of Gathering by Parker are technically for workshops and other large events than meetings. But there’s useful lessons in both for thinking about any work-related gathering of humans.

Rubick talks about restructuring meetings once they get too big

Good overview on running remote brainstorming sessions by Ciszkowski

Getting a sense-of-the-room with spectrum voting like Fist of Five as described in this article by Calabrese is a quick way to get input from everyone in the middle of a discussion

Would this be valuable to someone you know? Share the public post:

Next week my plan is to discuss the mechanics of actually facilitating the meeting well. Are these topics useful to you? Any meeting horror stories or success stories you want to share? Any meeting debugging issues you’d like to ask about? Hit reply, or email me at [email protected].

For now, on to the roundup!

Managing Teams

Defusing Dramatic Conversations - Jack Coates

This is the article I alluded to above, about how to run an improptu meeting to pass on bad news.

The context here is a product leader who’s gotten bad news that they have to pass on, but the advice here is good in general.

The meeting: “We have a change to handle. Here’s what it is, here’s why, and here’s a rough plan for how to make it happen.” […] “I know it sucks, but this is the situation. Let’s discuss the details tomorrow.”

Some key advice Coates gives is:

Bad news is hard. Get any strong negative reaction out of your system first, on your own.

Act quickly to pass on the news.

Have an improptu meeting right away with as many of the affected people as you can quickly manage, or use an existing meeting if one with the right person/people is coming up soon enough.

Pass on the news unemotionally, and with initial rough next steps.

Bad news is hard for them, too. The purpose for this meeting is to pass the news on, not to engage or problem solve right away. Give them some time to react, too.

Overcoming The Resistance - Paulo André

How to make decisions that don’t sink - Mike Petrovich

A lot of our job revolves around decision making - making decisions ourselves, or creating the environment in which decisions are made.

It can be terrifying! I remember the literal sleepless night I had deciding who to hire for the first time. (As an aside, at the time what was keeping me up was concern about not hiring “the best possible” person than about hiring a poor fit to our needs - my thinking was just so backwards. Ah well, live and grow.)

In research we could study something for a year or two before committing ourselves to some clear unambiguous choice or decision or conclusion - indeed, it might be irresponsible not to. As a manager or leader, that year of quiet contemplation is not a luxury available to us.

André’s article tackles that fear head on. He counsels paying attention to any hesitation around making a decision, and being aware of it. Then some simple approaches to combat that resistance:

Create a process and trust in it

Use things like the pomodoro technique to make small discrete progress and combat hesitation

80% is good enough - don’t procrastinate due to perfectionoism

Assess what went well and give yourself your own feedback loop.

Petrovich’s article focusses on the process piece, and in particular making decisions fast where reasonable so you can do a retrospective quickly and learn from it. The framework he has is:

Define the problem (and what a success would look like)

Identify the reversibility of the decision - if you can walk back a decision quickly and painlessly, which is often the case, speed run this process and reevaluate after a bit. Otherwise go more slowly

Select the people who should be involved

Define the evaluation criteria

Come up with ideas and pick some top ones

Decide

Have a retrospective periodically reviewing your decision.

Petrovich makes an important point about looking back on your decisions:

Don’t judge the quality of your decision-making based on the outcome of an individual decision. Sometimes the worst outcome happens in spite of a good process, and other times you get lucky in spite of a bad one.

Decision making under uncertainty is, well, uncertain. You can make the most sensible decision available given what you know at the time and still have it turn out poorly. Annie Bett’s book Thinking in Bets is good on this, and inspired lots of other writing which is also good. When you’re doing retrospectives on the decisions, focus on what you can change (yourprocess around making decisions) and not what you can’t (the past decision, and the uncertainty you were operating under at the time).

Women Aren’t Promoted Because Managers Underestimate Their Potential - Kelly Shue, Yale Insights

While managers can consider real-world metrics in evaluating performance, potential is more abstract—and that might make it more subject to bias. […]. Specifically, Shue and her colleagues found that while women receive higher performance ratings—they are 7.3% more likely than men to receive a “high” rating in performance—their potential ratings are 5.8% lower. The authors estimate that lower potential ratings explain up to 50% of the gap in promotions.

Sadly, this isn’t a new revelation - there are decades of existing research on this - but it persists, and we as managers and leaders would do well to have this in mind when we’re deciding on growth opportunities for team members as well as formal promotions.

Shue’s research and other work that she references tallies up the evidence, but doesn’t provide us any easy answers for how to make things better. Depending on the type of opportunity under consideration, we could focus more on actual performance (which seems less biased) rather than potential. But that’s not a perfect solution; when we’re assessing suitability for new responsibilities, past performance may not be a strong enough guide.

One thing we can do is be aware of this bias (which doesn’t only affect us male managers!) and try to take it into account. Another is to ramp up new responsibilities in modest and frequent steps through delegation, so we’re less often putting ourselves in the position of guessing about potential to make big leaps.

Random

Another piece of evidence for “coming from research gives us superpowers” - a well thought out 4000 word essay about how to deal with ambiguous research or R&D problems as a software developer.

ChatGPT for pair programming, which is pretty much consistent with my experiences playing with these generative AI solutions - it’s more like mentoring a precocious junior than a machine that you drop an API key into and it spits out a finished solution, and that's more than enough to be valuable in clarifying our thoughts and getting work done.

That’s it…

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox. And if you don’t do please consider subscribing:

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your team,

Jonathan