Let’s finish up the last in the series on running good recurring meetings.

In our time in academia we probably have not seen a lot of well run meetings, and we certainly weren’t trained how to run one effectively.

And that’s a real shame, because meetings at their best are collaborative work sessions for alignment, problem solving, decision making, and driving momentum. They are important tools! Meetings that don’t waste their potential is a missed opportunity. And our team members’ and colleagues’ time is too precious to squander on poorly run meetings.

On the other hand, if you get a reputation for running meetings well (especially in an environment where that’s not usually the case), that will get you noticed, and may well get you invitations to meetings you wouldn’t normally get a chance to attend. Running a meeting well is a leadership skill even if you’re not the leader of the group you’re meeting with.

Now that we’ve leaned about meeting purposes (#143) and to take into account what the attendees will get out of the meeting (#144) we’re at what for many of us is the hardest stage - actually running the meeting effectively. That takes a more directive approach than we’re are probably used to. As with the earlier issues, we’ll talk about this in terms of recurring meetings, but these approaches work for any meeting.

Meetings have Chairs, Facilitators, and Note Takers

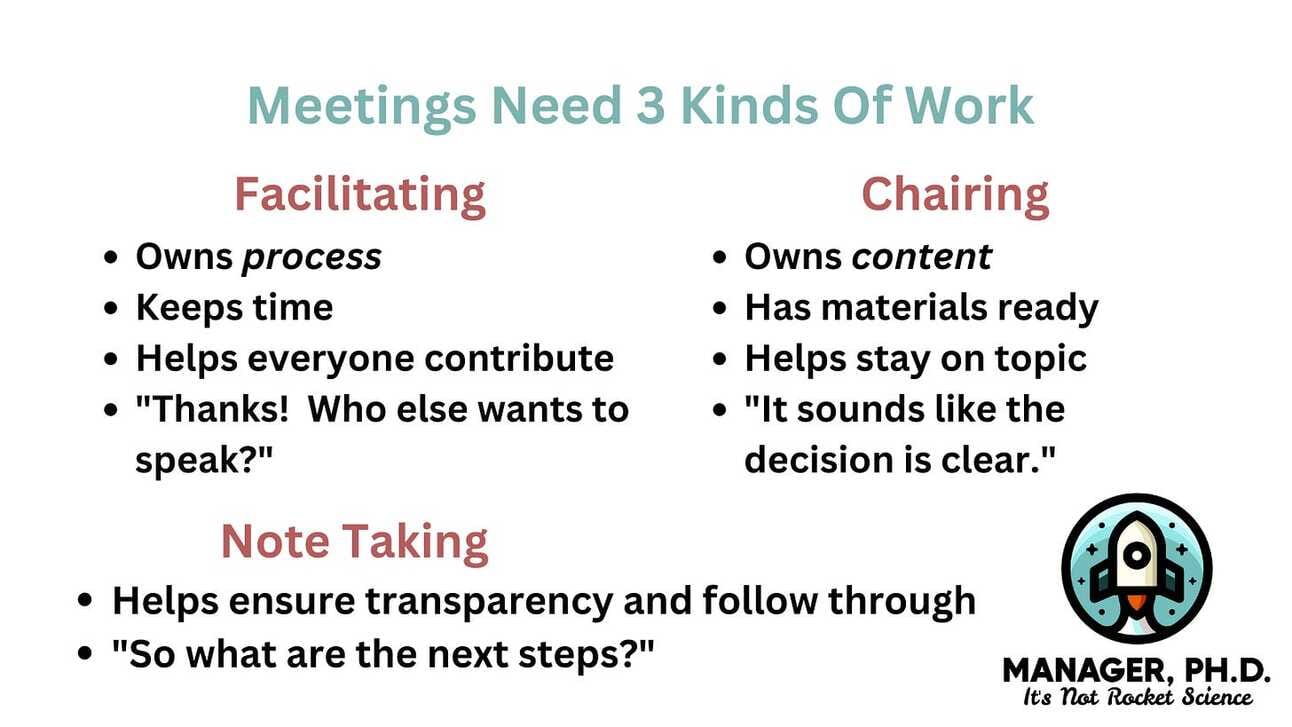

There is different kinds of work involved in running a meeting:

Meeting (or agenda) chairs is what we usually think of; they’re the person in charge of the meeting (or the agenda item within the meeting), and they’re the ones who will own the result from it (whether it’s the decision being made, the next steps resulting). By the nature of their role, they’re an active participant in the content of the meeting or agenda item.

Facilitating the meeting is to control the process of the meeting rather than the content - to make sure everyone who should speak gets a chance to speak (which might mean gently winding down someone else’s contribution), noticing if people look like they are lost or disagree, keeping things engaged and civil, and keeping agenda items to time.

Note taking is, essentially, controlling the post-meeting next steps; this responsibility is to record what’s necessary to document what’s happened and what will happened next.

These roles exist and this work is done for every meeting, but the responsibilities might be shared between people, or one person might have all roles. In a one-on-one, for instance, you as manager have the responsibility to facilitate when necessary, but both people probably “own” their parts of the agenda and take their own notes.

Note takers

In larger meetings, having the roles be more explicitly defined and assigned becomes valuable. For a very small meeting, the chair can probably also facilitate and take notes. The meeting getting paused because the chair has to catch up and write a note about something - “hold on, I just have to write that down” is a sign that this is starting to break down and a separate note taker becomes needed.

So assigning a note taker is very valuable. This tends to pull someone out of active participation, so it’s best to rotate this role, with everyone taking a turn, and possibly having someone else take notes during a section where the person who is taking notes needs to contribute.

It’s worth talking about what notes should look like.

In academia, we tend to take notes like it’s class, and everything that’s being said might be on the final exam. For some kinds of meetings, like discussions with stakeholders to identify needs and their current experiences with the work of the team, that’s a pretty good approach - write everything down, distill it later.

But for (say) a team meeting, the sort of meeting that has an agenda, that’s not usually helpful. Usually in your meeting notes circulated afterwards, you just need:

What was decided, with a couple key points about why

Very high-level summary of any other topics raised

Next steps/todo items (who does what by when)

So a note taker only has to record in the moment things that would likely show up on that list. That means a very high-level listing of points being raised. The note taker should feel comfortable breaking in and asking for clarification/repetition if necessary.

Notes should be circulated very promptly after the meeting, and ideally posted somewhere widely visible. Meeting notes should be quite public as a default; transparency is our friend here, it helps people know what is going on and reassures them that they can know what’s going on without being invited to the meeting.

Facilitator

It becomes obvious when we need a separate note taker - either the notes are bad or the meeting discussion suffers.

The need for a separate facilitator, on the other hand, doesn’t necessarily have such a clear warning sign. That’s a problem! In a meeting much past five people or so, it can become very difficult to be an active participant in a discussion and to be paying attention about who is and who isn’t participating, and how, and to take action to bring in others. And if no one is doing the facilitating, there’s probably people who are systematically not contributing, which is demoralizing for them and a waste of their potential input for you.

The facilitator needs to:

Pay attention to who has and hasn’t contributed, and invite those who haven’t contributed yet to do so

That may mean gently winding up someone else’s contribution

Keep discussions on topic

Keep discussions on time.

This means being fairly directive.

If this meeting is with your team, and you’re the manager, it is much easier for you to be the facilitator than to ask one of the team members to facilitate their peers. That would mean you’d have to participate directly a bit less; if that’s an option for the topics being discussed, I strongly recommend it, at least for enough meetings to have modelled what you would like facilitation to look like. You’re the boss, you can contribute your opinion on a topic any time you like. Getting the other attendees to contribute effectively to the discussion is a priority.

Even as managers, it can be a little awkward redirecting someone’s contribution when they are running long or time is running short. I like summarization as a technique (“Thanks, X, I just wanted to make sure I understand - it sounds like you’re saying A then B, because C, is that right? Ok, great; what do others think on the topic? How about you, Y?”), which also helps the note taker. Or simply “Thanks for that, X! I want to make sure we get a chance to hear from everyone affected by this. Y, what are your thoughts?”, or “Terrific, let’s take a note of that. Right now we’re discussing D though, and we’re running short of time. Y, what’s your input on D?” Sometimes it may take a couple of iterations of this to get someone to wind up, but a bit of gentle firmness works wonders.

(What are your favourite techniques? Shoot me an email).

Parking Lots and Time Limits

It helps the facilitator and chair a lot if the agenda has two things:

Durations for discussions of agenda items

An item at the end called “other topics”, “parking lot”, “new business”, or “items arising” - all different names for the same thing.

Durations are clear enough; it’s much easier for the facilitator to keep a discussion to time if the time limit is written there in black and white.

The “Other topics” agenda item is intentionally a catch all, and its purpose is to keep earlier discussions on topic. When someone inevitably goes off on a tangent, the facilitator or the meeting chair can use that time slot to say “not now” rather than “no”. They can suggest saving that topic for the other topics agenda item, rescuing the earlier topic.

Meeting (Or Agenda Item) Owner or Chair

The Facilitator owns the process of the discussion; the chair owns the content, either of the whole meeting or of a particular agenda item. They’re responsible for making sure appropriate material was circulated before hand, for assigning to do list items afterwards, and for any decisions being made.

In a way this is the easiest of the three roles. Here the job is simply to make sure the most important points being raised are highlighted (which makes things easier for the participants and the note taker), to own and be clear about the process for decision making, and to crisply define followup tasks and make sure they’re assigned. The chair, owning the content, is the decider of what discussions are on and off topic, and so they’re the ones who should propose items get moved to “other topics”.

It is really important - especially if you’re the chair and someone else is facilitating - for the chair to defer to the facilitator about issues of time or winding up so other people can speak. That’s why it can be really valuable for you to facilitate and partly recuse yourself from charing where possible, at least for long enough to model the behaviour of a well-facilitated meeting. And when you’re chairing and someone else is facilitating, modelling that deference to the facilitator is vital.

Ground Rules And Retrospectives

Again, retrospectives (#128) are the key to getting better as a team. Quarterly or so, have team meeting retrospectives in your recurring group meetings, and get input on what works and what doesn’t. Maintain a list of what you decide collectively as ground rules, have them posted in the meeting agendas, and include them in onboarding materials. This shouldn’t be Robert’s Rules, just a concise list of things your group does to have good meetings. There’s no one set of ground rules for meetings that makes sense for every group - it depends on the humans involved and the kinds of discussions they need to have together.

And that’s it. None of this is rocket science. Our teams and their work are too important to squander their time in poor meetings, and it’s unnecessary. Good meeting practice takes being a bit more directive than we’re used to, and requires constant tending to. But choosing meaningful meeting purposes, having agenda items that are valuable to the attendees, and then running meetings in a way that visibly respects people’s time and their work makes for vastly better meetings and happier teams (actually true, we have data on this). Being known as someone who runs meetings well will help your reputation; and as you let the roles rotate between team members having them run meetings the same way, it’ll build their professional skills and reputation.

And with that, on to the roundup!

Managing Teams

Great people management is more than 1:1s - Flora Devlin

Devlin talks about the regular connection points, at different cadences, that build good working relationships with team members. Three of them will be familiar to Manager, Ph.D. readers:

Weekly one-on-ones;

Development chats (which work well in one-on-ones, but probably aren’t a topic discussed every single week); and

Devlin mentions a fourth one, though, which is interesting - regularly working with team members:

Bi-weekly work sessions: These are your space to work through problems together - whether that’s white-boarding new designs, understanding metrics and data, preparing for a board meeting. There’s a lot of work that happens where collaboration is invaluable.

Maybe for work- and results-focussed people like our community, it almost goes without saying that there’s value in touching base on the work of the team itself, not in a reporting status sort of way but on the work itself. But I think there’s value in calling it out as part of the regular rhythm of a successful manager-team member working relationship, and Devlin is making a good point I don’t see made elsewhere.

How often this happens would depend on the type of the work, but it’s interesting to look back and think of my most successful working relationships with team members, how many of those had the hands-on work time happening fairly regularly…

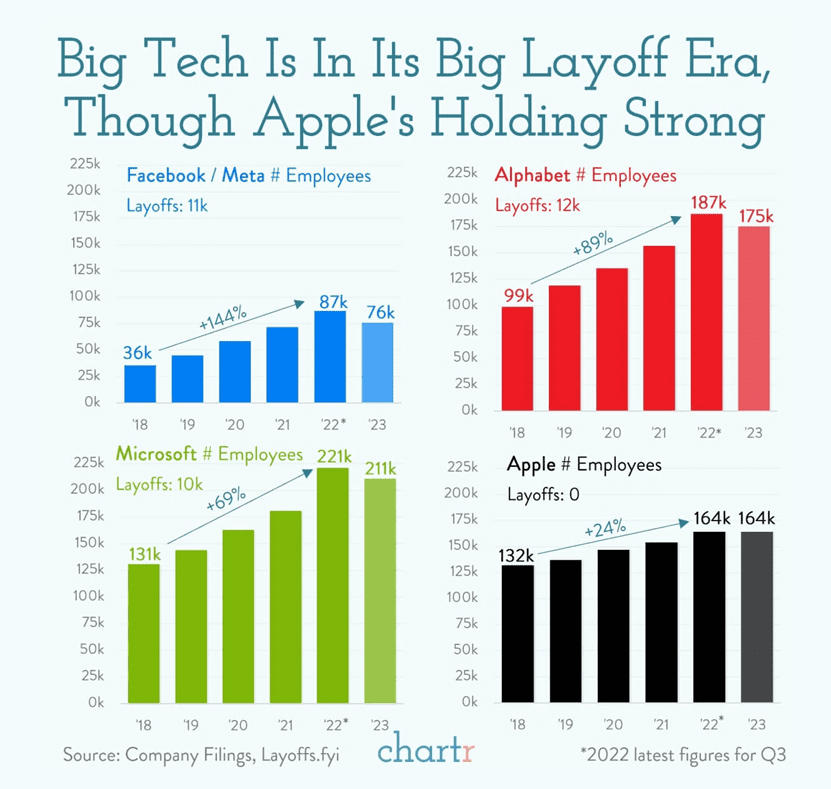

Were All These Layoffs Inevitable? Perhaps, But Here’s How It Happened - Josh BersinDespite Layoffs, It’s Still a Workers’ Labor Market - Atta Tarki, HBR

I’ve spoken with a couple of managers who are watching tech layoffs closely, and hoping that this means hiring for our own roles will be easier.

I don’t think that’s how it’s going to work. Firstly, as Bersin points out, big tech companies’ layoffs are typically only bringing them back to roughly 2021 staffing levels — and I don’t remember 2021 as being an amazingly easy year to be an RCD hiring manager.

Secondly, the roles that overlap for the skills we are looking especially hard for - those that combine mathematical modelling and software dev skills, or AI/ML/data science skills, or HPC positions, or devops roles - by and large aren’t the ones being pared back en masse.

Finally and most importantly, most tech jobs are not at Big Tech firms. We don’t typically lose out to FAANG (the now slightly out of date acronym for Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix, and Google)-type companies for our candidates; rather it’s the vastly larger number of roles of tech roles in “regular” businesses which are our biggest competition, if only because there’s vastly more of these jobs.

Tarki walks us through recent labour market numbers in the US, pointing out that despite the headline grabbing numbers of these layoffs, layoff numbers are actually quite low economy-wide (at least in the US).

“Quit factor”, or How the industry lulls itself to sleep with “bus factor” - Alexey Makhotkin

“Quit factor”, “burnout factor”, “bored factor”, heck, “vacation factor” - Makhotkin is right here. There are lots of reasons why it’s a bad idea to have all the knowledge for a key technology/product/project/process tied up in one person. Talking about it in terms of less likely events like the person leaving or getting in an accident downplays those other issues.

In our smaller teams it’s an easy trap to fall into, but it’s worse in some ways. We are leading teams of experts. Not building robust mechanisms for sharing and distributing knowledge means we’re not growing our team as much as we could be.

Random

Two spaces after a period is faster to read, at least for other two-spacers. Crucially, this means we two-spacers can communicate faster with each other and so get a jump on the one-spacers when the typographic revolution comes.

This video about what to do if anything when you get bad coffee in a café is a better tutorial about giving feedback to organizationally distant peers than half of the management and business material out there.

You know how you’ve always wanted to sync a pendulum clock to a Caesium time source to create the worlds most accurate grandfather clock? Dr. Daniel Baluch at CERN has some ideas.

That’s it…

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your team,

Jonathan