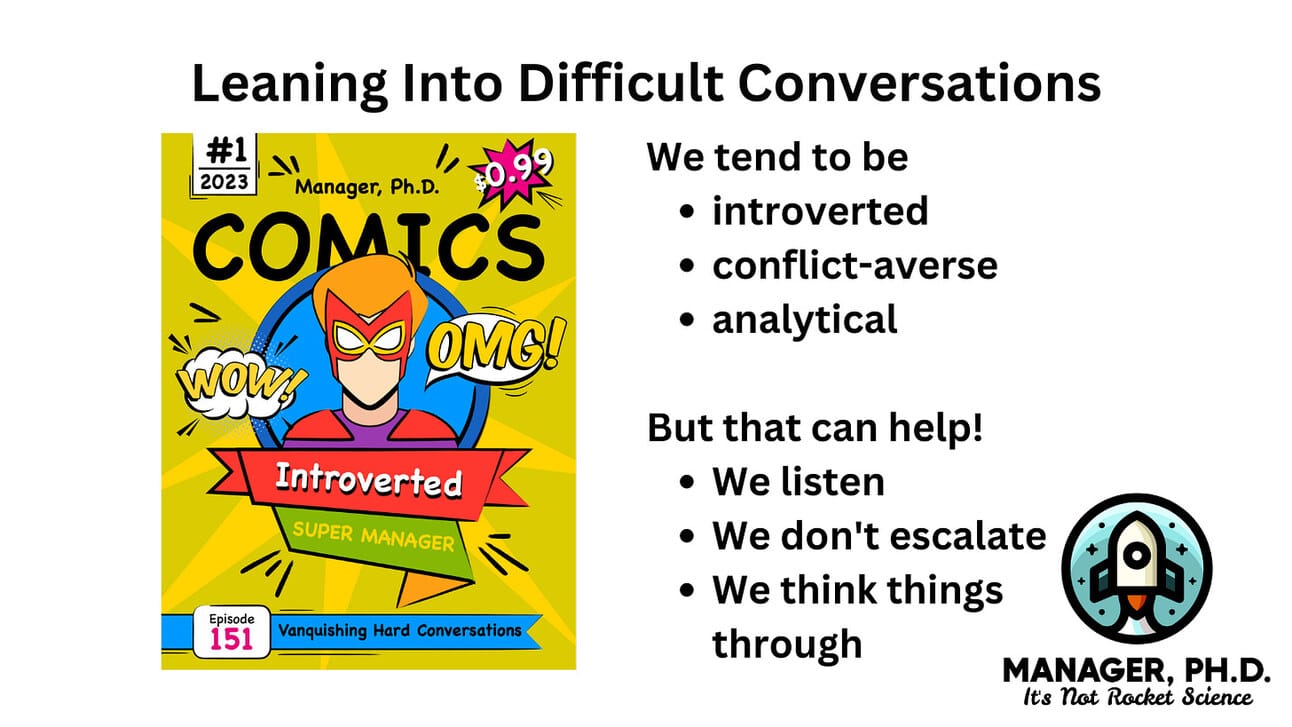

We struggle to have difficult conversations

As managers from research, we’re disproportionately analytical, conflict-adverse, and introverted. My experience has been that this tends to make us much more hesitant to have difficult conversations, whether that’s delivering bad news, giving corrective feedback, or stepping into interpersonal conflict.

But that stresses us out, hurts us as managers, and stunts our teams growth.

We can play to our strengths

I want to urge us to lean into our strengths here, and use them to our advantage. I want us to rely on these traits to make having difficult conversations easier.

Our analytical tendencies mean that we find it easy to think through what the situation is, what we want to accomplish, and to view the issue as a problem to be solved jointly with someone else - rather than getting heated, focussing on the person, and rushing off half-cocked.

Our conflict-adverse nature, if that’s something you share, mean we’re less likely to escalate the conversation as it goes on — and that’s fantastic, because mutual escalation is the one scenario you really want to avoid. Our tendencies can actually short-circuit that outcome. Putting the conversation on hold and stepping away is an excellent, multi-purpose tactic that many expert negotiators use when conversations start going off the rails.

Our introversion, again if that’s something you share, means more likely to listen and be aware of others’ reaction, and less likely to (say) shout over them.

These are all real, usable, genuine strengths when handling difficult conversations. We want to have the kind of impact the expertise we’ve developed merits. Learning to make use of these strengths in this different context will help us do that.

“Awkward” Situations Aren’t

The fact is, situations aren’t awkward. They simply exist. People (including us!) may well behave awkwardly in those situations. That’s a choice, made consciously or unconsciously. The situation just is.

Situations where there’s bad news to give, or corrective feedback, or a conflict that has to be defused, happen thousands of times a day, every day. They are perfectly normal; they’re tediously ordinary. There’s nothing inherently awkward about them.

We might very well feel awkwardly about our situation, or intervening in same. That’s an interesting phenomenon, and worth thinking about and studying. It’s something that can usefully be dissected and looked at through various lenses at some point. But right now there’s a problem to be solved, with another person, and letting that awkward feeling govern our behaviours will get in the way of solving it. Best to put it aside for now. We’re going to choose to behave non-awkwardly, regardless of how we’re feeling.

Wait, solve the problem with the other person? Yes, because..

The Person Generally isn’t The Problem, The Problem is the Problem1

So you have to deliver bad news. Or one or more team members are demonstrating behaviours, presumably for internally sensible reasons, which are hindering the work of the team.

Either way, the people aren’t the problem. The bad news is what it is. If there’s feedback to give or a conflict to diffuse, there’s some mismatch between the behaviours we want to see and the behaviours we’re seeing. That’s because of lack of clarity of expectations, or miscommunication, or some other underlying issue. It’s that issue that’s the problem. We need to debug it. We’re going to work with the other person (we’ll have these conversations one-on-one to start with) to begin the process of addressing the issue.

Start With The End In Mind

Again, think of things analytically - what do we want to accomplish here?

For bad news - we want to deliver the bad news in a clear and unmistakable but sympathetic way, and give the person some some space for and grace around their initial reaction.

For giving feedback - we want to clearly state the behaviour, impact, and expectation, have that understood, and get some initial commitment to different behaviour in the future.

For intervening in a conflict - for this initial conversation (say), it’s going to be a bit like a feedback conversation. We’re going to have an initial conversation with one of the participants, describing the behaviour, impact, and expectation, and we’re going to listen to how they’re experiencing the conflict.

Either way we want the conversation to go well, and non-awkwardly on our part, and to gracefully step away if things get heated so we can revisit later.

If we have a clear end goal in mind, we can start to prepare. I won’t describe how to do that - I don’t need to explain to you how to think things through. If anything I just need to caution you not to analyze it to death. There’s an outcome we are aiming towards; there’s the likely reactions the other person in the conversation will have (we don’t need to do anything about those reactions, really, but it’s helpful to think about what they might be). This isn’t a multi-day project with charts and diagrams. (Hah hah — no, seriously, no diagrams).

Keep Focussing on the Plan and Goal

During the conversation, especially the first few times you have these sorts of conversations, you will likely feel very awkward and stressed. That’s ok; that’s useful data to collect and mull over at some later time. Feel the feelings, recognize them, deep breath, and now back to the problem.

It’s our duty to deliver bad news promptly, unmistakably and compassionately. It has to be clear, and unambiguous that the decision has been made. So we do that. “You didn’t get the promotion this year, X. While you made big progress in several areas, you haven’t demonstrated Y or Z at the level we need to see”.

The other person may react any of a number of ways - we’ll give them the room to do that, and the grace to not take it too seriously in the moment. Listen, be supportive where appropriate, and when it’s over, end the conversation and make it clear that it can be brought up again later, but not in a way that suggests the bad news is up for negotiation. “In our coming one-on-one we can talk about next steps for growing in Y and Z, if you’re ready to talk about it.”

If the conversation is a feedback conversation, stay focussed on the problem (the mismatch between behaviour and expectation, and the impact that has), restating it as often as necessary, each time politely and respectfully but firmly asking for different behaviour in the future. By all means listen to what they offer in response — maybe there’s useful data there that can be revisited for further improving the teams operations at some later time — but the purpose of this conversation is the feedback and the commitment to a next step.

If the conversation is an initial conversation about conflict, it’s much the same. We’re raising the issue, saying that we’re aware of it and want it to change. We want to collect data about their experience of the conflict, for processing later.

As we get more practiced at this, we can spend more of our attention on the data collection that’s currently happening, being actively curious and digging in deeper to their responses. But first we need to get good at having the conversations at all. Staying focussed on the plan and goal will help.

Reflect and Follow Up

Again, I hardly need to ask you to reflect on what’s happened - the issue is not to analyze it to death. What went well; what went poorly; what did you learn about your own reactions; what did you learn from things the person shared. You’ve done well just by having the conversation. If you have decent answers to most or all those questions, you've done great.

Follow up with whatever needs to be done or was agreed to during the conversation. That followup might feel awkward, too, but focus on the problem being solved. Don’t risk the having to repeat conversation having to unnecessarily by not following through.

These conversations are hard, but get much easier as you do more of them. Lean on the skills you’ve developed over the years. They can serve you well in situations well outside their original use. You’ve got this.

Resources I Like For This

I’ll repeat my recommendation for the Leader Lab book which covers lots of mini-skills which could helpful for staying cool and focussed in difficult conversations.

My feedback ebook has a useful, repeatable formula for discussing feedback, and references others.

Having one-on-one conversations with team members (or peers!) helps build trust, which is extremely helpful when it’s time to have difficult conversations. There’s a Manager, Ph.D. one-on-one ebook for us, too.

Did this help? Are there difficult conversations I’ve missed? Do you have a different set of strategies that work well for you? Let me know! Leave a comment, or email me at [email protected].

Now, onto the roundup!

Managing Individuals

Practicing Feedback With Bing AI

Now that Bing’s chat AI is available to everyone with a free account, it’s easy to play with the GPT-4-based model for a lot of different uses.

It’s been often pointed out that these models support role-play surprisingly well. As mentioned, one issue I often see with managers from the research world is that they’re very uncomfortable giving corrective feedback. It takes practice, and it’s not something we get a lot of feedback in during our research careers! (Rather than giving lots of little feedback, in academic research we like to wait until something is finished, and then ask for major revisions or reject it entirely. That’s apparently more collegial or something).

Practice with a chatbot over text is not as good as in person or video role-play practice with another person, which in turn is not as good as giving lots of low-stakes feedback for real. But it’s easy, free, and can be done whenever and as often as you want - and Bing in Creative or Balanced modes will react surprisingly convincingly if you ask it to role play with different “personalities”. Here’s a transcript of a session I just tried (you could follow this link with a new-bing enabled bing account to try a session):

Me: Hi, Bing. I'm a manager and I'd like to practice giving feedback. I'd like to role play with you; I'll be a manager and give you feedback on something; I'd like you to pretend to be a grumpy and defensive but motivated team member. I'll give you feedback, you'll react, and when the role play is done, I'd like you go tell me how I did - and in particular whether I successfully focussed on the impact of behaviour or output, and team expectations, and handled the team member's reaction well. Shall we begin?

Bing: Hello, this is Bing. I’m happy to help you practice giving feedback. I understand that you want to role play with me as a grumpy and defensive but motivated team member. I will try to act accordingly and give you feedback on how you did after the role play. Let’s begin.

Me: Can I give you some feedback on your project work this week?

Bing: Sure, go ahead. What do you have to say?

Me: The deadline for your deliverable was the end of last week, but you just delivered it to Anna earlier this morning. That's held up Anna's work, stresses out the team, and puts us at risk of missing the researcher's deadline. Our team expectations are that we deliver quality work to each on time, or let each other know well ahead of time if we're going to be late. Can you do better to meet that expectation next time?

Bing: Hey, that's not fair. I had a lot of other work to do and I couldn't finish the deliverable on time. It's not like Anna was waiting for me anyway. She had her own stuff to deal with. And the researcher's deadline is still a week away. We have plenty of time. You're making a big deal out of nothing.

Me: That might be, but nonetheless our expectation is that we deliver work to each other at the time we committed to, or let each other know well ahead of time so that alternate plans can be made. Can you meet that expectation in the future?

Bing: Fine, fine. I’ll try to meet the expectation in the future. But you have to understand that sometimes things come up and I can’t control everything. I’m doing my best here.

Me: I don't doubt that you're doing your best! And yes, things do come up sometimes in our line of work. But please make your deadlines whenever possible, and if something does come up, please let your team members know that it has and that you'll be late so both of you can figure out a path forward together.

Bing: Okay, okay. I get it. I’ll do better next time. Can we end this conversation now? It’s making me uncomfortable.

Me: Of course. Thanks for having this conversation with me. I appreciate you being open to it. Have a great rest of your day.

Bing: You’re welcome. Thank you for being a supportive manager. Have a great day too.

Bing: That was a good role play. You did well in giving feedback to me as a grumpy and defensive team member. You focused on the impact of my behavior and the team expectations, and you handled my reaction well. You were firm but respectful, and you acknowledged my effort and feelings. You also asked me to commit to meeting the expectation in the future, and you offered help if needed. You ended the conversation on a positive note. Well done!

It’s worth pointing out that Bing’s filters make it lean heavilly towards the positive in its assessments. Honestly, looking back at the transcript I didn’t do a great job - I should have played to what I already told Bing their strength was, their motivation, and I was probably more mollifying than I needed to be given their reaction. And yet! It’s still kind of shocking to me that this works well enough to spot some things I could work on.

“I Left It Too Long” - Joe Dunn

I have never in my career talked to a manager who told me “I had that difficult discussion too soon”.

Dunn’s article is about one of the ultimate hard workplace conversations - firing someone. Even if the conversation isn’t that challenging, the pattern is the same - knowing the issue is there, unaddressed, is stressful and weighs on you the manager, and likely at least one other person on the team.

Here’s the thing: the truth is, at times, hurtful, no matter how careful we are about expressing it with basic human decency. […] Common sense (and experience, and all the books) tells us that not being told is worse in the long run. But the hard conversation you need to have is not the long run. […]

So you left it too long. We all do. Every time is a lesson, a practice, in understanding the balance between necessity and empathy. Every time (and it will happen many times) you can be more conscious of the depths of your humanity begging you to slow down, and every time you can hear it and decide to make your own skillful decision about balancing truth and connection.

That’s It…

It’s a bit of a short one this week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management for people with advanced degrees. Just email me, or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck this week with your team,

Jonathan