Manager, Ph.D. is a newsletter and community which helps people from the world of research reach their full potential managing teams and enacting changes. We’ve already developed the advanced skills to be exceptional managers; we just need help with the basics.

If you’re new to the community, drop me a note! Some past issues from the archive which you might be interested in include:

#111, “The Complete Intern Checklist"

#130, “Taking On A New Responsibility”

Plus of course the one-on-one and feedback guides.

And whether you’re new to the community or not, feel free to email me, or even have a quick chat with me about problems you have, or things you’d like to see!

Most new or otherwise uncertain efforts don’t succeed.

But often they don’t exactly fail, either.

For most of these efforts we take on, the biggest risk we face isn’t a anecdote-worthy catastrophic failure stemming from not faithfully following a pre-made plan.

The biggest risk of most new or uncertain things we try is of them just kind of fizzling out and halting. Or even worse, of the effort moving forward in a mediocre, crummy way, and then having it plod along, useless but never properly ending.

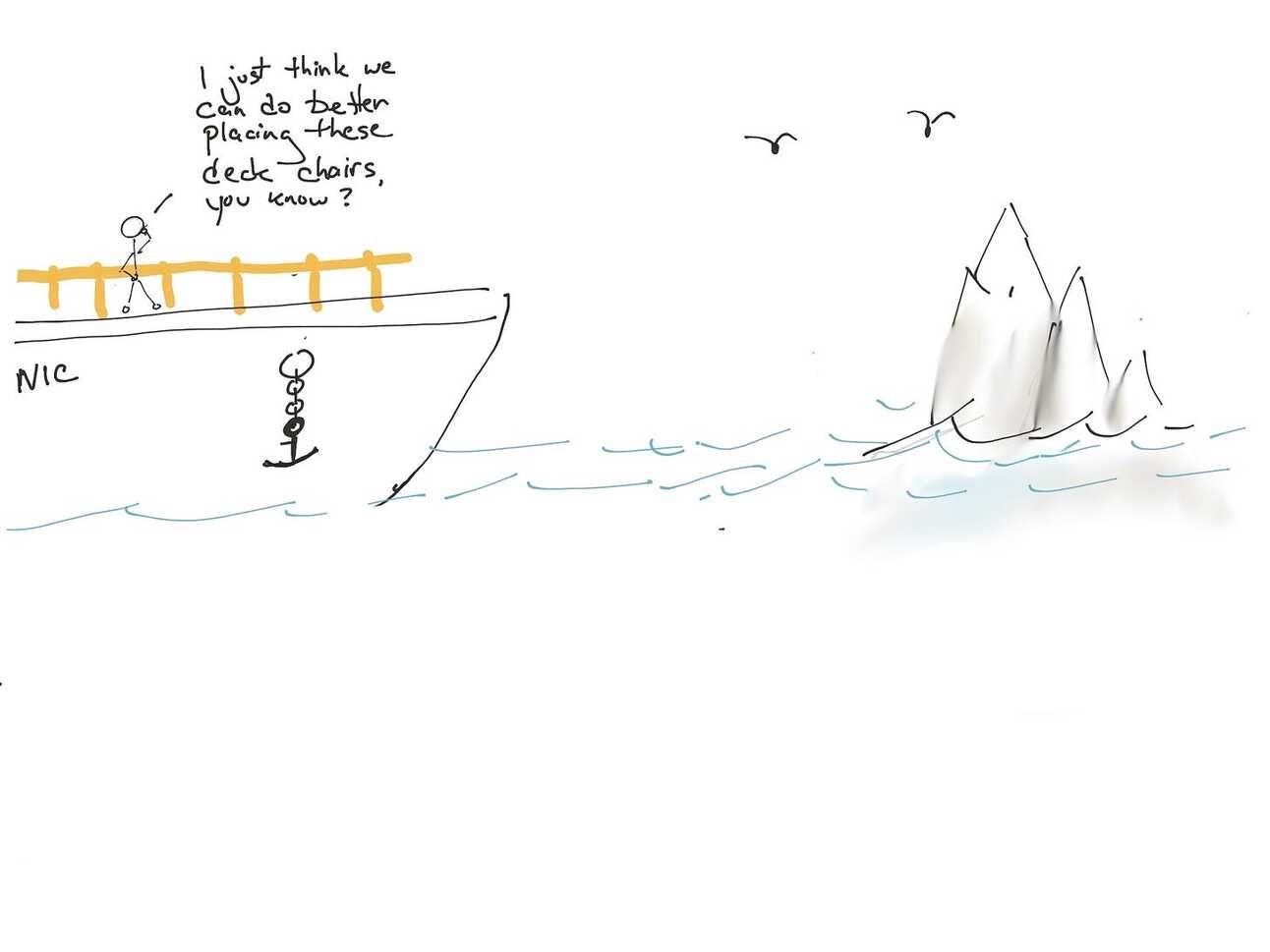

If we don’t pay attention to what the real big risks are of an effort, we greatly increase the chance of that risk becoming reality. If instead of navigating dangers emerging from the waters we instead try to control all of the details of the beautiful plan we made when we were ashore, we shouldn’t be surprised when things end poorly.

So let’s talk about most of the genuinely uncertain things we are charged with overseeing in our work.

The most common uncertain things we do as managers are fuzzy. Like trying to effect change in an organization (as in last issue, #162), or changing processes in our team, or building new collaborations with stakeholders or other teams, starting a new communications practice. There’s real uncertainty here about how to proceed, and it can even be difficult to tie down exactly what the best possible outcome is.

A major way I see experts like us flounder in these uncertain or ambiguous situations is that we like to try to Think the problem into submission. We’re smart! We have navigated lots of uncertain paths in the world of research. We sat down, came up with a plan, walked ourselves (and others) through it, and revisited periodically. Just trust the process!

That works really well when the biggest risks are contaminating the data with poor experimental techniques or analysis methods. If that’s the problem, then expertise, and carefully followed protocols, is indeed the solution.

But the situations I’m talking about aren’t like those. We’re uncertain about how to proceed, and the goals are ambiguous. Partly because they involve other people.

In those cases the biggest risk is the risk of the effort just kind of floundering and eventually sputtering to a halt. Not even actually failing properly, more like falling over half-way through. And our natural, deeply-ingrained desire to cling for life to a carefully pre-crafted plan will all but ensure that this is what happens.

(Another situation where I see this attempt to control the details, by the way, is when expert managers feel uncertain about the effort, regardless of whether or not it really is objectively all that uncertain. Delegating tasks (#93, #101, #123, #153) is a classic case. I’ll write more about delegation in another issue).

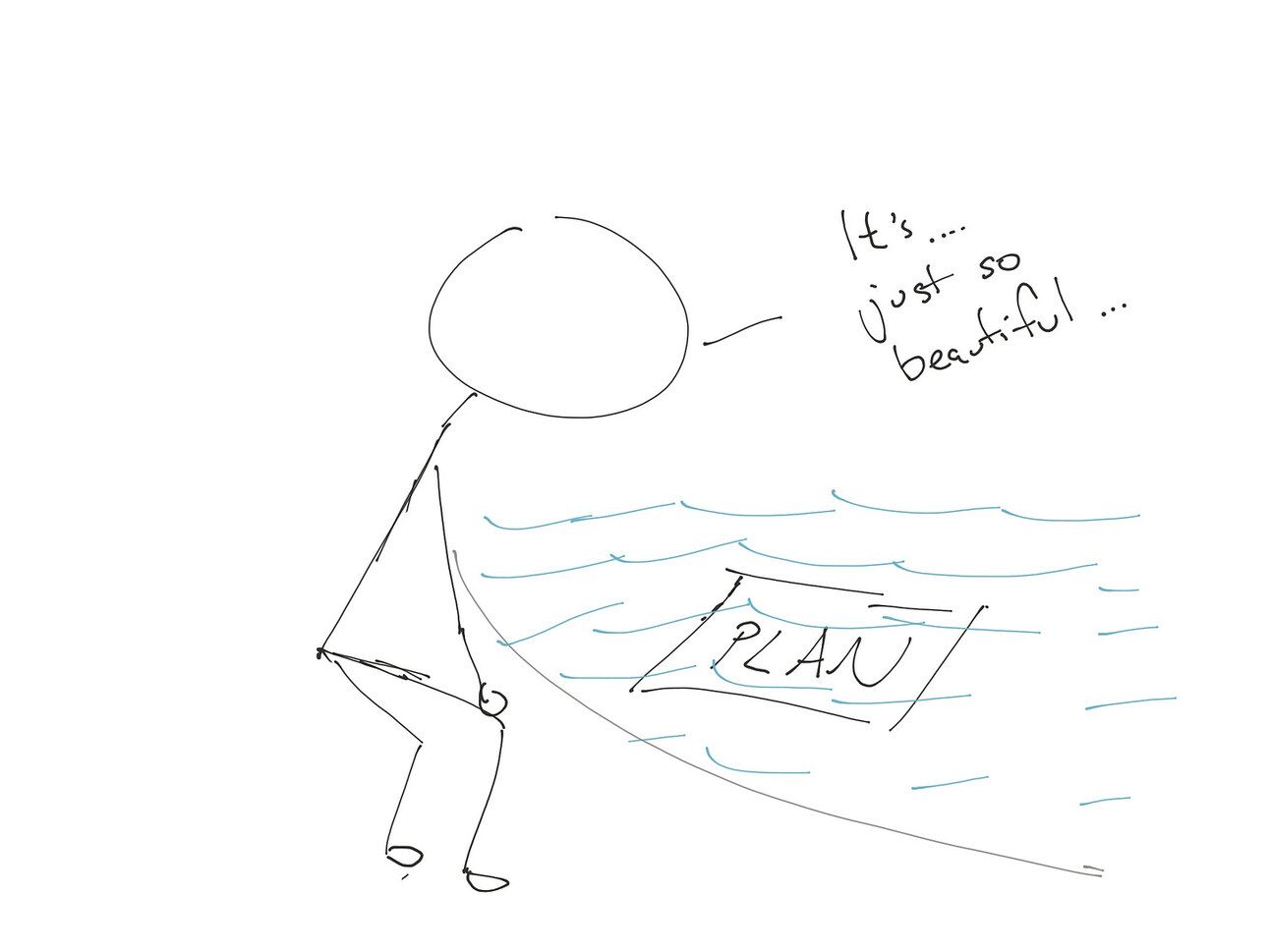

And, look. This is harsh, but I’m saying this because I genuinely care about people like you who step up to lead, who want to use our expertise in this way, and I want them to succeed. That plan you made? It doesn’t actually matter. What matters is the outcome, not the plan. People like us, we tend to put a lot of thought, energy, creativity into our plans. We tend to put a lot of ourselves into the plans. Like Narcissus, we kind of fall in love with that reflection of our creative work. And we need to stop, because it’s not healthy for us, our teams, or the efforts the plans are for.

In situations where the dominant risk is not of catastrophe, but of a quiet failure, of just getting bogged down and stopping well short of any meaningful outcome or even learning opportunity, the big risk mitigation is simple: keep things moving. Ensure the effort keeps making progress, even if opportunities to do so take it off the original plan. That doesn’t mean doing random things! That means continually prioritizing reasonable-looking forward progress over what at the beginning we thought would be best possible next steps.

This is the same idea as other forms of managerial decision making (#158). For the vast majority of the things we do, it’s better to make lots of good-enough decisions quickly, and make a point of learning from them, than to make occasional very good decisions after long periods of quiet contemplation. Heck, probably the only quick way to learn how to consistently make very good decisions is a frequent feedback cycle of fast good-enough-decision followed by learning.

We shouldn’t downplay how hard this is for experts like us. Deciding and moving quickly, constantly roughly steering in a promising direction represents a massive in approach compared to what we’ve been trained to do and rewarded for in the first part of our careers. It’s different, feels unnatural, and honestly seems risky and exhausting compared to the considered, careful, well-researched, cited and footnoted approach we’re used to taking.

And yet it’s a skill we can learn. We know how to be flexible and adaptive in our research, in the lab, in our hypotheses. We’re used to, in the pre-planning stages, holding lightly to ideas and goals. We can take that flexibility and learn to apply it not just to the crafting of a plan but to its execution. Really! It just takes practice. And then we have two very useful and complementary mindsets, tools in the tool chest, for guiding an effort to a successful conclusion.

Just think about what the actual risks of an endeavour are, and then apply your approach accordingly.

Have you seen efforts fizzle out? What caused it, and what do you think might have been done differently? Or did you successfully keep it going - how? Let me know - email me at [email protected], or just hit “reply” if you’re reading this in your email.

And now, on to the roundup!

Managing Individuals

A model for changing behaviors - Jens Rantil

Do Managers Really Have Power Over Employee Motivation? - Marta Simeonova

Rentil writes about the Fogg Behavioural model, a behavioural design model for changing behaviours. The argument goes that a prompt (like you giving feedback, coaching, or direction to a team member) can trigger behaviour change if the recipient, at that time:

Is motivated to make the change

Has the ability to (a) make the change and in particular (b) do the new behaviour

If they don’t have the ability or the motivation, then all the prompting in the world isn’t going to change much. It’s possible that very high ability could partly compensate for very low motivation (since it would be very easy for them to do), or vice versa (if they’re motivated enough to develop the ability).

This is a useful way to think about whether a requested change is reasonable, or to investigate why a requested change didn’t happen. Rental offers the example of getting people to write unit tests in the software they’re developing - they can (for instance) reward or recognize the new behaviour they want to see (possibly increasing motivation), or they can make it easier to do the new behaviour (have good infrastructure and templates for writing and running tests, do training, speed up how fast they run…)

Taking a perhaps broader meaning of “motivation”, Simeonova asks whether we can actually motivate employees. She concludes, I think rightly, that we can’t make create motivation, but we can encourage it not to fizzle out by

Getting to know the person

Find out what motivates them

Provide them opportunities to be motivated by those things

I’ll add that while we can’t directly motivate people, we can 100% un-motivate people by piling on unreasonable expectations and disregarding their input or contributions. That needn’t be permanent, but it takes longer to fix than for it to happen.

I often talk about implicit vs explicit expectations (make everything explicit!), but Leto likes and advocates for using different terminology — expectations vs agreements. E.g. we might well think we’ve made some expectation explicit, but surely it’s much better to actually have actually come to some agreement, with an individual or even with a team, about the standard being set.

I could see this being useful! Leto’s argument makes the case, and I’ll have to think about it. I’m not sure if signing paper is necessarily helpful, and I don’t think we should fool ourselves into thinking that a team member “agreeing” to something a manager says is quite as bilateral and equal as “agreement” might suggest, but certainly using this language makes it very clear the difference between me just expecting something and a team member and I having a shared understanding.

Managing Teams

Related to the idea of pushing forward, learning as we go, Fisher writes about the importance of accepting failure (failure + learning is vastly better than things just fizzling out and never finishing one way or another), with a discussion of a study I’d not heard of:

Mark Rober, CrunchLabs founder and ex-NASA engineer […] designed an experiment examining human reactions to the risk of failure. […] Unbeknownst to the participants, two slightly different versions of the puzzle existed. One group started with 200 points, remaining unaffected by failed attempts. The second group also began with 200 points, but lost five points each time they failed. Despite these points being purely symbolic and void of real-world value, the group facing no point-loss played the game 2.5 times more and succeeded 16% more than their counterparts.

By not feeling punished for unsuccessful attempts, the first group moved faster, played more games, and so as a result got better.

Fisher also points me to the “3X framework” which he wrote about earlier, and is new to me - the idea that efforts in this framework focus on exploring, expanding, or extracting (an certainly not all at once).

My stupid noise journey - , dynomight

The author here describes a problem that I think we have even worse than most - the curse of knowledge, being sure

I don’t want to spoil this article by summarizing it. Suffice it to say that, just like clinging to a plan because we’ve created it, it’s very very easy for people who have developed some hard-won expertise in an area to cling too tightly to what we think we know about a situation even when it’s not in our area of expertise!

We know from our previous careers that experimental results trump theory every time. Doing something quick to learn, even when we think we know the answer, can save a lot of time and effort compared to relying on what we’re pretty sure is the case.

Managing Projects

IBM Project Manager Certificate: My Student Review - Elizabeth Harrin

Harrin, whose review of Google’s Project Management course and certificate we covered earlier, takes a look at IBMs PjM course on Coursera and is largely positive about it for full-on Project Management. I argue that’s more than most of us need; but if some of us are doing work where we benefit from the full machinery of something like PMBOK, and if so, this might be of interest.

Managing Within Organizations

This can apply to any relationship, including with one of your team members. I find, though, it’s more common for it to be an issue between people in different parts of the organization. Maybe a peer, maybe someone organizationally more distant.

Maybe you played a role in the trust breakdown. Or maybe the problem predates you, and you’re coming into one team that has a long and fraught history with another; and yet you see that the two teams need each other if they’re going to succeed.

The bad news is that rebuilding trust is going to take lots of effort, and time. The good news is that Majors has written a great piece about how to do it, based on experiences between Majors and her cofounder after a rough patch. She recommends:

Do it anyway

Acknowledging (to that person!) that it’s hard, either beforehand or after

Communicate positive intent

Speak tentatively (that, at least, tends to be natural to us)

Go out of your way to be friendly in the conversation, because “When trust is low, the lack of frills can easily be read as brusque or rude.”

Relatedly, be careful about the stories going on in your own head like “they just got right into work, what a jerk”. Majors recommends the book Crucial Conversations, which is very good about this.

Take breaks when needed (if you feel yourself getting cross or panicky or…)

Engineer positive interactions, even if you have to invent them: “It might seem artificial at first, but look for chances to have any sort of positive interactions, and seize them.”

Give people the opening to do better the next time

Remember the difficulties but value the effort

Managing Your Own Career

I, like many of us, am profoundly — almost comically — bad at asking for what I need from others. That’s one of the skills that my current job is basically forcing me to get better at, but it’s still hard.

Osmani gives us the pep talk we might need. There are immediate personal costs (selling ourselves short, limiting our learning); and ripple effects downstream (those we’re asking for get clearer about needs, there’s payoffs down the road).

Osmana then gives us some suggestions about how to get better: defining clearly up front what we need, practice in safe spaces (by the way, I continue to think doing role-play practice with ChatGPT or Bing Creative is a very underrated way of practicing conversations), and being ready for know but expecting a yes.

That’s It…

And that’s it for the week! I hope it was useful; Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share with me about how a newsletter or community about management for people like us might be even more valuable. Just email me, leave a comment, reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox, or schedule a quick Manager, Ph.D. reader input call.

Have a great weekend, and best of luck in the coming week week with your team,

Jonathan